Money, banking & insurance

Why 2009 isn’t Like 1929

A few months ago a number of highly-strung financial journalists were reporting on the end of investment banking, the death of capitalism and the next great depression. They could still be right, but I doubt it. Now that we have had time to reflect and not merely react, it is apparent that 1929 and 2009 are quite different and the current situation resembles 1990-91 and 2001 (and maybe 1987) more than 1929.

But even this is simplistic. Students of history will note that each crisis has its own characteristics and triggers. As the Economist magazine reported, ‘the parallels between the speculative mania that ended in October 1929 and the housing bubble are seductive but misleading’. To start with, in 1929 the economy was in deep trouble long before the stock market bust and most people assumed that it was a less serious repeat of the 1921 troubles when the economy shrank by 25%. As a result the Federal Reserve in the US initially did nothing. In 2008/9, in contrast, economic data is abundant and governments around the world were fairly quick to step in.

One of the reasons that a downturn in 1929 turned into an extended depression was that monetary policy was too tight. The result was that 1,000 banks closed their doors in 1930 (300 had already done so during the first half of 1929) and it is estimated that 44% of all mortgages in the US were in arrears. Unemployment in the US hit 25% (with no government safety net) whereas today unemployment in the US it is around 6%. This could climb to 10% but it’s still not 25%. Moreover, there aren’t people standing outside banks demanding their money back or people on street corners in vast numbers asking for something to eat. Yes it’s the most serious economic crisis many people have seen, but only just. Remember, for example, that between early 2000 and 2002 the Nasdaq fell by nearly 80%, or that between 1987 and 1991 almost 2,000 US banks failed due to speculative real estate lending. Conclusions? History is useful for decoding what’s going on but the most important thing is our immediate surroundings and this does not yet suggest that the current financial crisis will resemble 1929. Not yet anyway.

Ref: Wall Street Journal (US), 14 October 2008, ‘Black Friday 1929 revisited’, K. Blumenthal. www.wsj.com See also The Economist (UK), 4 October 2008, ‘1929 and all that’. www.economist.com

Source integrity: Various

Search words: Economy, 1929, 2009

Trend tags: Globalisation, recession, anxiety

The Dangers of Credit Default Swaps

The current financial crisis was largely caused by greed, excessive debt and networked risk.* But buried within this unholy trinity is another factor. Credit Default Swaps (CDS) are privately traded derivatives contracts that conceal a plethora of dangers. Essentially, CDSs provide insurance on risky bonds. The market is totally unregulated and almost no information is publicly disclosed, with the result that almost nobody knows what exposure they’re got. And don’t think that CDSs are an obscure market either. It’s been estimated that the current value of CDS contracts is US $54.5 trillion. That’s significantly more than the total amount of corporate debt in the US. What’s more anyone can buy a CDS contract, they can be agreed to in a minute, they don’t require any cash upfront and you don’t even need to own a bond to buy a CDS contract on it.

If you were being kind you’d call the CDS market an unregulated, uncapitalised insurance market but casino gambling might be closer to the truth. You can bet on any event and, and this is the really scary bit, you don’t know who is holding the other side of the bet and the risk can be transferred along the line until it ‘disappears’. At least with a casino the relationship is transparent. Are these instruments of mass financial destruction going away? Not a chance. The best we can hope for is that they are regulated in some form. If they are not they will almost certainly start another round of risky behaviour that could start another nasty chain reaction.

* OK, plus ultra-cheap money, an over reliance on credit, over-confident bankers, misguided regulation and deregulation, hedge funds, shadow banking, CDOs, CBOs, and other 21st century derivatives, over-investment in housing (as opposed to technology during the tech boom), an abject failure of credit rating agencies and Asian savings.

Ref: Fortune (US), 13 October 2008, ‘The $55 Trillion Question’, N. Varchaver and K. Benner. www.fortune.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: CDS, derivatives, risk

Trend tags: Connectivity

China Crisis?

Not long ago economists were talking about de-coupling, the idea being that regions like China, India, Russia and the Gulf States were immune to America’s financial crisis. But now it’s clear that the world is massively connected and that an American or European downturn will deeply affect everyone else. This is not to say that countries such as China will perfectly replicate what happens in the US, but simply to say that there will be serious consequences.

The most likely scenario is that China’s growth will slow from double figures to around 8% or 9% but therein lays the problem. China Inc has prospered in recent years, much more so than the Chinese people. This is not to say that things haven’t improved for the average person in China. They have. Roughly 200 million people have been taken out of poverty. However, the unspoken contract between the deeply authoritarian Chinese government and the people of China is that the people won’t complain too loudly about the government just so long as the economy keeps growing and they eventually become richer – and 8% annual growth appears to be the magic figure. The fear, for the government at least, is that anything much less than this could spark large-scale unemployment and social unrest as laid-off urban factory workers join disposed peasants and environmental campaigners calling for radical change.

India is perhaps in a similar position but, ironically, India’s weakness is also its strength. India has a more flexible (some might say chaotic) system and it can cope with serious disagreement. Having said this, India could still be in trouble. India’s workforce is increasing by 14 million workers a year (25% of the world’s total) and it could be argued that India’s recent economic success is largely confined to a relatively small number of highly educated workers employed in IT services.

But back to China. How can China avoid a major downturn? One option would be to devalue to Yuan to help exporters, but this could backfire. What China needs to do is use it’s vast cash surplus to stimulate domestic demand rather than spend more money on export industries or property development. Currently a mere 38% of Chinese GDP is domestic consumption, a figure much lower than in most other countries worldwide.

Ref: Newsweek (US), 7 October 2008, ‘The perils of thrift’, G. Wehrfritz, www.newsweek.com See also The Economist (UK), 13 December 2008, ‘Suddenly vulnerable’ and The Economist (UK), 20 September ‘Beware Failing BRICs’. www.economist.com

Source integrity: Various

Search words: China, India

Trend tags: China

The Immediate Future of Banking

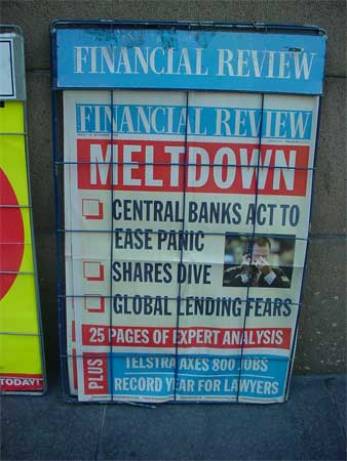

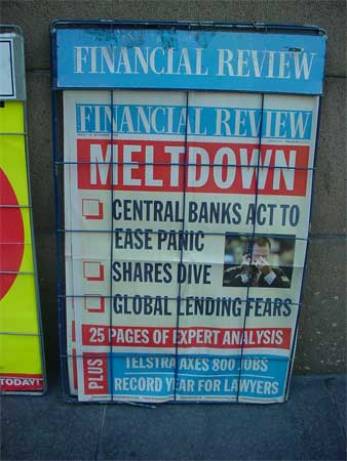

It is sometimes easy to forget that the economic crisis is just that. It is an economic crisis, not a meltdown, and its cause has more to do with the internal structure and regulation of the financial services industry than with world geopolitics or economics. Underneath the crisis, the world economy is still in relatively good shape. Credit and confidence will remerge and with them will come a series of opportunities.

So what are some of the longer-term implications of the current situation? The first set of opportunities relates to financial institutions in developed regions such as the US and Western Europe. In these regions, investment banks and retail banks will continue to converge, resulting in a polarisation between a handful of very large players and a plethora of smaller firms. The opportunities associated with this include the potential for new local and boutique banks and new niche models. In other words, the centre will not hold. The larger institutions will all divest assets to increase capital, boost their presence in emerging markets, raise capital through rights issues, readdress risk management practices and simplify their product portfolios in order to boost profitability.

The second area of opportunity lies with financial institutions in emerging economies (especially the BRIC and N11 markets). The institutions have generally escaped the worst exposure to toxic assets and debt and are therefore in an enviable position to further consolidate local lending, especially through retail banking, and also expand in developed markets either through start-ups or, more likely, through acquisitions.

The final area of opportunity (or threat depending how you see things) is for national and international regulation. One could argue that inferior or misguided regulation was a primary cause of the current crisis but you can be certain that a consequence of the crisis will be more legislation, not less. Again this will probably benefit the larger institutions.

Ref: Strategy + Business (US), 14 October 2008, Resilience Report ‘Taking a calmer view’, K-P Gushurst, I de Souza and V Wallace. www.strategy-business.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: Banking, retail banking

Trend tags: -

Every Cloud has a Silver Lining …

Ten days last year witnessed the nationalisation, failure or rescue of the world’s largest insurance firm, two of the world’s biggest investment backs and two giants of American mortgage lending. As a result, consumer and business confidence is in the gutter. But it’s not the end of the world. It’s not the start of WW3 or the outbreak of a global flu pandemic either. Yes, the current crisis is a big deal and compares with some of the worst most people have ever seen, but governments around the world are talking to each other and have a variety of tools at their disposal to sort the problems out. They can nationalise banks and other firms, they can suspend trading on markets and renegotiate mortgages. They can also print money.

This is not to say that the future is all rosy. It isn’t. Unemployment will rise, inflation will increase and people will feel less secure. Nevertheless, there are a number of silver linings embedded in the dark economic clouds. First up, oil prices are falling and cheaper house prices are good news for people that don’t have a house but would like one. But, most of all, the situation is a wake-up call for people that have been used to having it all. The problem, in a nutshell, is that individuals, institutions and even whole countries have been consuming more than they have been creating.

Debt has become the norm based on the idea that markets went up, but never came down. We had all become too reliant on money we didn’t have to buy things we weren’t prepared to wait for. For example, household debt in the US rose from US $680 billion in 1974 to US $14 trillion in 2008. The average US household also owns 13 credit cards and 40% of these cards carry an outstanding balance compared to 6% in 1970. But this is all nothing compared to government debt. In 1990 US national debt was $3 trillion. By 2008 it was $10.2 trillion. Moreover, much of this debt has been hidden.

So what’s next? Recent government attempts to stimulate the economy by giving money away or by telling people to shop are akin to giving a drunk more to drink. What’s needed is sensible investment in hard infrastructure projects (roads, schools, hospitals and so forth). In short, we need things that our children can use in the years ahead, not another television made in China. Another thing that must happen is that the financial services industry has to shrink. In 2007, for instance, 30% of S&P 500 profits came from financial firms, many of which could be deemed ‘unproductive’ in terms of delivering real products and services.

Ref: Various including Newsweek (US), 20 October 2008, ‘There is a silver lining’,

F. Zakaria. www.newsweek.com The Economist (UK), 20 September 2008, ‘What’s Next?’ and The Futurist (USD), November/December 20008, ‘Incentivizing thrift’, A. Cohen. www.wfs.org/futurist

Source integrity: Various

Search words: Economy, economic crisis, recession

Trend tags: Debt