Money, banking & insurance

Quick, the bank is closing

The old fashioned image of a bank as a grand, imposing building populated by august men in suits has long gone. Welcome to the smart-casual iPad-carrying cashier in yet another pseudo coffee-shop. Thanks to online banking, footfall (that means people) in branches in the UK is dropping by 20% a year while transactions done on mobiles doubled in 2013.

The Big Four all closed bank branches in 2014 and, before that, 2,153 UK bank branches closed between 2002 and 2012. The European Central Bank says Britain has only a third of the number of branches available in Germany, Spain or Italy. (In some Spanish banks, you can even buy a ham or a bicycle as well as make a deposit.)

The branches that remain are being remodeled internet cafe-style, with self-service machines, iPads, computer terminals, cheery seating areas and new ways to get service, such as videoconferencing and even Twitter. Cashiers no longer sit protected behind counters, but roam around looking helpful, with iPads. Banks now prefer to use ‘face to face’ time for higher-margin services, such as mortgage applications, investment advice or dealing with complaints.

Some 6,500 employees of Barclays are being upgraded to better-paid, customer-facing positions, to sell specialised products. Meanwhile, 1,700 lost their jobs in November 2013. The bank has now trained 7,000 ‘Digital Eagles’ (so named to reflect its logo) to help Barclays customers in the branch, and to go into the community to help people learn digital technologies. They run ‘tea and teach’ sessions about, for example, setting up email, sending and receiving money online, Skype and how to shop online. The bank says the idea is not to sell banking products, but to help the public understand the ‘benefits of digital’.

Judging by our parents, there will be a few very perplexed older people walking into banks this year. They just want to talk to a person or get some money – they don’t want to be directed to a machine they have to learn how to operate. Unfortunately, why would banks be interested in appealing to the older generation when their future customers, the digital natives, are so much cheaper to serve? Then again, in most countries it's those aged 55+ that hold most of the money.

Ref: Financial Times (UK), 12-13 July 2014, ‘Ipad generation drives banking shake-up’ by S Goff. www.ft.com

www.barclays.co.uk

Source integrity: *****

Search words: cashier, branch, footfall, mobiles, Barclays, Royal Bank of Scotland, self-service, videoconferencing, Twitter, ‘face to face’, costs, Germany, Spain, ‘digital eagles’, ‘tea and teach’.

Trend tags: Digitalisation, casualisation

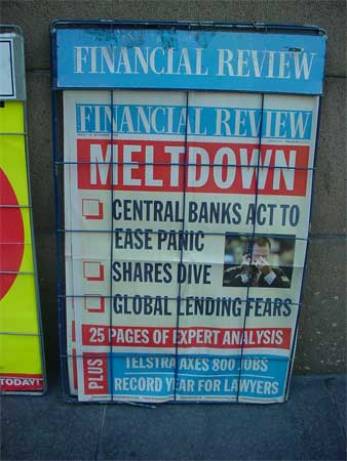

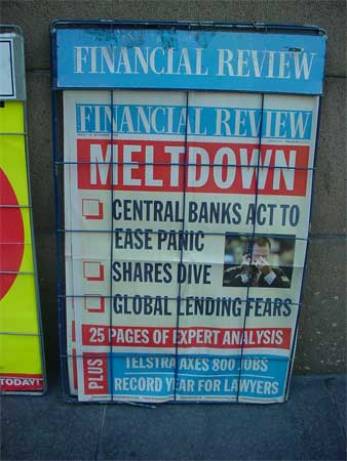

Deflation and weak demand in Europe

The prospect of deflation in Europe has some commentators wondering if this is the world’s biggest economic problem. The inflation rate is only 0.3%, well below the benchmark of 2% and, considering Europe provides a fifth of the world’s output, this could cause the collapse of the euro and even the eurozone. The euro fell to $US1.20, its lowest since June 2010 when Greece was first bailed out.

The president of the European Central Bank (ECB) says the problem is not so much deflation – lower oil prices are good - but demand is weak and that is not so easy to stimulate. There are 45 million people out of work in Europe, 40% youth unemployment in Italy and Spain, and consumer confidence is low after continual talk of austerity measures, structural reforms, and reining in deficits.

If consumers expect prices to fall, they will stop spending and borrowing and, with lower demand, loan defaults rise: this happened in the Great Depression. Falling oil prices only add to this scenario. (See our story, The global effects of cheaper oil).

One answer is ‘quantitative easing’, otherwise known as buying sovereign government bonds and the ECB will consider this possibility. The size of the bond purchase is not so important as sending investors a “strong and credible signal”, according to one chief economist. This is not necessarily a popular move. Germany prefers that the weaker countries undertake more structural reform rather than receive yet more money.

This is a hot potato and, by the time you read this, things may have changed. It will be interesting to watch how continually growing unemployment in all the rich countries continues to impact on their economies and even on the workings of capitalism itself.

Ref: The Economist (UK), 25 October 2014, ‘The world’s biggest economic problem’. Anon. www.economist.com

The Guardian (UK), 3 January 2014, ‘European Central Bank boss hints at stimulus to fight deflation’ by J Rankin.

www.theguardian.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: Japan, China, recession, reforms, inflation, deflation, debt, oil prices, unemployment, demography, infrastructure, government bonds, European Central Bank (ECB), Euro, Eurozone, manufacturing, Italy, Spain.

Trend tags:

Data – the more, the better ?

How much is a company worth, especially one with no physical product and no profit? If you are Twitter, a $US23 billion market capitalisation at the end of 2014. This is a lot of money, even for a tech company. The value is in all the personal contributions of people who use Twitter to communicate. Each person on their own might not offer much, but in the aggregate, they all provide a massive set of data that becomes potentially valuable to the companies that store it.

As far as data goes, in the digital age - the more, the better. While Twitter is looking at ways to attract more advertising (see our story, What next for Twitterdom?), it is sitting on a growing pile of data offering insights about the stock market, food safety, or politics, you name it. While governments traditionally held the lion’s share of data about their citizens, now internet companies do.

While internet companies have started giving users more control over their data, this could stop if these data become more valuable to them. After all, investors will start to expect a decent profit when they are paying such high price/earnings ratios (around 70 times earnings for Twitter). But what’s good for investors – closed data - may not be good for people in the long run.

Thanks to open data, citizens and activists have been able to question government actions, improve transport and encourage the effectiveness of health and police services. It would be a step backwards if people’s personal data were kept from them then used for corporate gain.

At the same time, our data are becoming more intimate, for example, health and lifestyle information from wearable gadgets (see our story, Strap on your health monitor). How can we make sure there is a balance between protecting the data that matter most to us, and benefiting from the value that comes from giving our data away to companies like Twitter?

Ref: New Scientist (UK), 16 November 2014, ‘The law of large numbers’. Anon. www.newscientist.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: tweet, Twitter, information, data, advertising revenue, access, open data, government.

Trend tags:

Why the digital wallet is still empty

Paying by phone was a great idea, but it’s not really happening in America, the UK or Australia. This is not because people don’t have smartphones. But restaurants and retailers have to be set up to accept mobile phones as payment and, unfortunately, this means they have to install new terminals – and pay the same fees to process the transaction. They may as well swipe a credit card.

Apple Pay is a new kid on the block in America, which will be accepted at 220,000 outlets and for reportedly lower fees than usual. It uses near field communication (NFC) that links phones with terminals, and ‘tokenisation’, where the devices exchange digital vouchers rather than card numbers. This will cut down on fraud. Users with an iTunes account can simply touch the fingerprint reader on their device. For early adopters of Apple’s new smart watch, all they will have to do is raise their hands.

People are confused by mobile payments. There are already too many mobile payment systems, including Google Wallet, Softcard, CurrenC, PayPal, Stripe, and Square. Even Starbucks has an app, where customers pay by holding an image on their phone up to a scanner and get loyalty points. There is no reason why petrol stations, grocery shops and public transport could not do the same.

Customers and merchants are accustomed to using credit cards and trust them to work as they always have. Perhaps mobile payments will have more immediate potential in the developing world, where there are 2.5 billion ‘unbanked’ people. They already have mobile phones and are used to using them rather than computers to go online. Meanwhile, in the West, we will have to wait for more contactless terminals or for younger users to become influential with their early adoption of the technology.

Ref: Forbes (US), 5 January 2015, ‘Why you’re not using Apple Pay’ by G Marks. www.forbes.com, The Economist (UK), 18 October 2014, ‘Emptying pockets’. Anon. www.economist.com

Source integrity: ****

Search words: smartphone, Apple Pay, Google Wallet, Sprint, Softcard, PayPal, credit card, terminals, near-field communication (NFC), ‘tokenisation’, fingerprints, fees, Starbucks, loyalty points, iBeacon, developing countries, finance, mobile payments.

Trend tags: Digitalisation

Catch up if you can

Economic convergence is defined as the process by which poorer countries catch up to rich countries over time. According to the Economist, this is a temporary phenomenon and the trend is starting to reverse. Other commentators point to recent IMF figures that show convergence is still occurring, but unevenly across countries, and unevenly in pace.

Just as the GFC looked dismal for the rich economies in aggregate (though not for individual countries like Australia with its commodities boom), so economic convergence can look gloomy when all developing countries are considered together.

The fact remains China saw double-digit growth in the first decade of this century, and even India and Brazil did well. While China has slowed in pace, its 7% growth rate still doubles total income every decade and this is sustainable. Other emerging economies did well in this decade, 7.6% per year, according to The Economist. Latest forecasts by the IMF say advanced economies are growing at 1.8% compared to 4.6% in emerging economies. It’s not as fast as in the previous decade, but that does not signal the end of convergence, only a change of pace.

Convergence happens, even in countries that lack savings, are geographically difficult, corrupt or seemingly unreformable, for example, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea, Thailand and Indonesia. While many of these countries will take a long time to catch up with the rich countries, the fact they could get even halfway is positive. IMF data show 'emerging and developing Asia' has grown steadily at 6.5% recently and is forecast to continue like this.

The idea of catching up at all is an interesting one. It implies that rich countries have it all and everybody wants to be just like them. Is there anything we have that they might not want?

Ref: The Interpreter (Aus), 16 September 2014, ‘The end of economic convergence? Not quite’ by S Grenville. www.lowyinterpreter.org

The Economist (UK), 13 September 2014, ‘The headwinds return’. Anon. www.economist.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: economic convergence, developing countries, GDP, growth, living standards, World Bank, Soviet Union, Taiwan, Singapore, Brazil, China, trade, manufacturing, infrastructure, corruption, commodities.

Trend tags: Convergence