Money, banking & insurance

How doomed is consumption really?

There have been many pronouncements about the future of consumption, in the wake of 9/11, the GFC, or just plain recession. Whether it is true, or just wishful thinking, many commentators believe we are becoming less focused on buying things and more attuned to frugality or loftier activities, such as spending time with family. But how true is this? And even if we had momentarily stopped spending, will it last?

In America, personal spending has fallen since 2007 and savings was above 6% this year, compared to zero a few years ago. Americans had less money to spend, because of unemployment, the housing crash and the stockmarket tumble and the wealth effect predicts that people spend less when they get poorer and spend more when they get richer. But consumption did not crash for long and, this year, rose four months in a row. Most of the drop in consumption in 2008 came from buying less petrol and fewer cars (perhaps a good thing).

Forecasters of future consumption should note that the 1990-91 recession caused only brief frugality and the gentle world of simplicity and trading down did not last. After 9/11, there was no prolonged change in behaviour. And the Depression did not turn Americans into Scrooges – after the last world war, the consumer society really started in earnest. It seems unlikely that this downturn will usher in non-consumerism if the Depression couldn’t do it. It seems Americans are just born to shop – and the rest of us are happy to join them.

Ref: The New Yorker (US), 12 October 2009, ‘Inconspicuous consumption’, by James Surowiecki. www.newyorker.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: spending, frugality, wealth effect, GFC, recession, 9/11, Depression, consumer society, retail sales.

Trend tags: -

Mobile money in developing countries

Mobile phones are not usually associated with poor people but a new idea – mobile money – will allow those in developing countries to send and receive cash. It is a fast, cheap and safe method, and allows them to focus on other productive tasks. Mobiles also compensate for poor infrastructure, such as dangerous roads and slow services, giving a boost to economic growth.

The best example of mobile money is in Kenya, run by M-PESA, and serving 7 million users (just under 20% of the population). Young urban men use it to send money to their families in the country, and others to pay school fees or taxi drivers. Incomes in households using M-PESA have gone up 5-30% since the start of mobile banking. The service also gives people access to a form of savings account, although it cannot pay interest for regulatory reasons. Mobile banking is safer too: people in the Maldives will get mobile banking next year, because many lost their savings in the 2004 tsunami.

There is a group of people not so in favour of mobile banking and that is the banks. After all, they don’t want mobile operators working on their patch. Some banks see the opportunity and are getting together with mobile operators. Regulators, in turn, are concerned that mobile banking will be corruption-free and may object less if banks, with their more formal rules, are allowed to be involved. Overall, it seems like a creative idea for what is now standard technology, and it is worth applauding anything that helps the poor get richer.

Ref: The Economist (UK), 26 September 2009, ‘The power of mobile money’. Anon. www.economist.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: mobile phones, Africa, M-PESA, banks, Kenya, mobile operators, MTN, telecoms.

Trend tags:

Concentration risk

The banks are getting bigger. In America, the Big Four control nearly 40% of the country’s banking deposits, half its mortgages, and 66% of its credit cards. That is concentration, and each merger (eg, JPMorgan Chase) got the government nod.

You might expect that financial muscle of this order would lead to lower costs for credit cards and higher interest rates on savings, in the same way that supermarkets pass on their savings. But you would be disappointed. In fact, the reverse is true. They often charge more and pay lower rates on deposits, than smaller banks.

You might also expect customers to vote with their feet. But the costs of switching to another bank have become onerous, now that the customer takes on so much more of the banking work. Switching a loan, for example, can cost about a third of the loan’s annual interest rate. This is one reason why the brands of banks can be so tarnished, yet it makes no difference to their client base. In uncertain times, people are even less likely to switch, especially if they think banks are basically all the same.

An added advantage for big banks is that having a large market share means they more easily win business in IPOs. And winning more business gives them a bigger market share. An MIT paper found that banks were usually hired on the basis of market share rather than their performance – you don’t have to be good to be big. The trouble with big banks is that too much concentration increases risk. The next crash could be even bigger than the last – and we know who will suffer.

Ref: The New Yorker (US), 12 October 2009, ‘Why banks stay big’, by James Surowiecki. www.newyorker.com

Source integrity: *****

Search words: Citigroup, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, interest rates, deposits, loans, “switching costs”, refinancing, size, brands, Wall Street, market share, IPOs, megabanks, concentration.

Trend tags: -

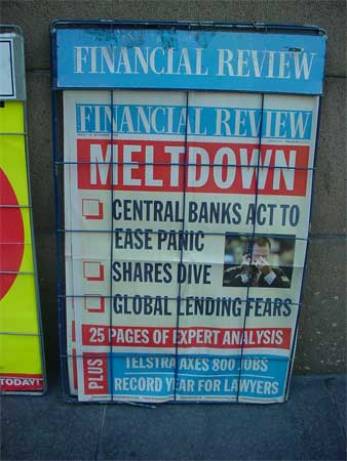

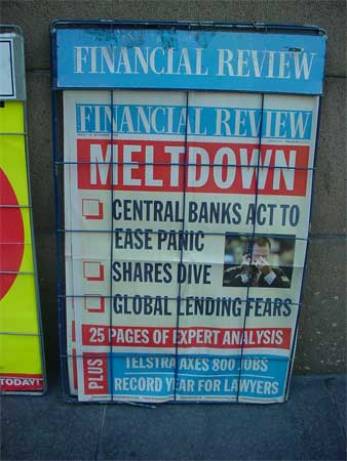

Soon-to-be-old current events

I have always wondered if people in their homes after work, sitting round dining tables, really do sit there and discuss the day’s current events. Or whether they are more concerned about the cost of groceries at the corner shop, their auntie’s failing health, and the kids’ school marks. You could argue that current events, whatever they are, will soon be old, like yesterday’s newspapers. So is there any point in lingering over them? In a recession, aren’t people just worried about how they, personally, are going to get along?

Current events are being compared with the Depression (oh pleeeeeease), as if that were a reliable indicator of what will happen this time. But is it possible to compare its mass industrial unemployment with today’s post-industrial, middle class, white collar downturn? People in the 1930s weren’t worrying about their superannuation portfolios or the value of their renovations. In fact, the middle classes today are in much better shape. They are just wondering how their futures will pan out and what their new normal will be. Their overriding sense of uncertainty will be the driver of this generation, in whatever they do decide to do next.

The Depression teaches one very positive lesson – the country recovered, and it brought economic transformation and a consumer boom. This may be little consolation to people now, especially those who have lost their jobs and their share portfolios, but they are part of an economic cycle that will turn. As the pace of life now is so much faster than during the 1930s, it is highly likely we will soon forget about this period as quickly as it came.

Ref: The Atlantic (US), ‘Life in (and after) our great recession’, October 2009, by Benjamin Schwartz. www.theatlantic.com.

Source integrity: *****

Search words: Recession, GFC

Trend tags: -

Christ and the GFC

Here is a fascinating idea: one of the contributors to the GFC was America’s new prosperity churches, which teach that everyone can have a big house and be rich. When this message comes from the pulpit to thousands of Latino immigrants, all struggling to make it in America, it sounds powerful. When the ministers were once mortgage lenders or have friends who are willing to make high-risk loans to eager borrowers, the stakes are even higher.

A recent Pew Internet survey found 73% of Latinos agreed with the statement, “God will grant financial success to all believers who have enough faith”. In fact, around 20% of America’s 260 churches teach the prosperity gospel. So it is no wonder that many churchgoers took out sub-prime loans believing they too could have a big house. The growth of the prosperity churches even follows a similar path to the hot spots of foreclosure – the exurban middle class and urban poor. Most of these churches were built in the Sun Belt, also the area hardest hit by the GFC. It is a compelling idea.

When Christ overturned the tables of the moneylenders in the temple, he wasn’t thinking that one day, churches would preach prosperity in his name.But the idea that Jesus blesses believers with money arose strongly during the wealthy 1990s and, in some ways, is mirrored in the secular belief that you can have what you want if you just believe you can.

This kind of positive language is very common among American motivational, business, and so-called “spiritual” teachers. Rajneesh was another one, who had almost 100 Rolls Royces as proof that money was no hindrance to spirituality. It will be interesting to watch the progress of the prosperity churches and see whether they continue to flourish in the face of the crash. You read it all here first (or second if you read the Atlantic).

Ref: The Atlantic (US), ‘Did Christianity cause the crash?’, December 2009, by Hanna Rosin. www.theatlantic.com.

Source integrity: *****

Search words: God, money, churches, GFC

Trend tags: -