Money, banking & insurance

Exogenous and endogenous economic shocks

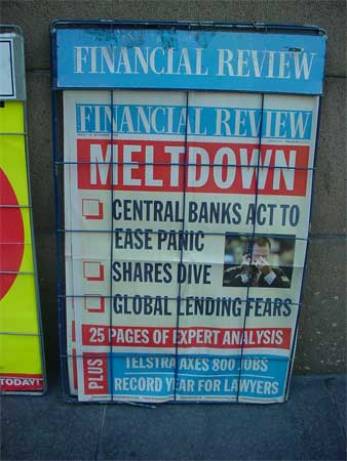

If you’re in the habit of making predictions, you might have thought that oil at US $60 a barrel would have brought the world economy to its knees. Equally, you might have thought that suicide bombers in London would have caused all sorts of economic problems. Both events have occurred but the predicted consequences haven’t. So what are the most likely external threats for 2006 and 2007? A US invasion of Iran is a possibility, but one which looks less and less likely with the continued troubles in Iraq. The death of King Fahd in Saudi Arabia could lead to either a collapse of the house of Saud or the creation of a reform movement backed by the EU or China, leading to oil prices rising to US $100 a barrel or the oil supply being turned off altogether. Another possibility is that China’s economic dominance will lead to nationalist and protectionist economic policies in the US and Europe, resulting in a trade war. These are all plausible scenarios, but future threats are more likely to come from within (the so-called endogenous threats). Examples include the US housing bubble bursting, the US Federal Reserve squeezing monetary policy too far, or the EU slipping into deflation (or even stagflation) due to its ageing workforce and poor productivity. And if demand from the US or Europe slows significantly, this could in turn lead to an economic crash in China due to the country’s export-orientated economy.

Ref: Financial Times (Asia), 9-10 July 2005, ‘The long view: Worst economic threats are not external’, P. Coggan. www.ft.com For commentary on the stagflation threat see The Economist (UK), 7 May 2005 ‘Stagflation, the remix’, or Barron’s (US), 7 February 2005, ‘Handling the truth’.

What are banks for?

Banking is an essential part of everyday life in western countries, but should banking services be provided by banks? Banks make their money by using yours. The really smart ones even charge you for it. They do a lot more besides, such as offering wealth management and financial planning, which is good, because in the future the banks may well lose control of deposit-taking and transactional services. Part of the problem is trust. Regulators want to open the banking system and make it more transparent, which will allow ordinary people to see how the banks create profit. People are already becoming more aware of how much money the ‘greedy banks’ are making, which is also putting pressure on the regulators to open up the market (high profits being seen as a sign of market inefficiency). Add to this a pinch of globalisation (more competitors from other countries) and add some technical innovations (more Internet-based business models and mobile payment options) and some people are left wondering why, in the age of instant communications, does it take four days to clear a payment through a bank? So, if change is in the air, where is it going to come from and what should the banks be doing about it? The biggest short-term threat is probably foreign banks with economies of scale. Then there are the monolines – specialist players (often from abroad) who seek to dominate a specific niche. Finally, and in the longer term, there are competitors from outside the industry. Most paradigm-busting innovations come from outside an industry and in this case the list would include everyone from mobile phone operators and other retailers to tech companies and social networking companies.

Ref: Various including The Economist (UK), 21 May 2005, ‘Survey of international banking’. www.economist.com

A tale of two economies

Is there more than one global economy? Indeed, can a country be in periods of growth and recession simultaneously?

For example, in Australia the economy is up in some areas and down in others. It’s the same story with property. In some Australian States, real estate has reached the limits of growth and people are saving or paying off debts, while in other States property values are still increasing and people are still spending. Why the discrepancy? The reason is globalisation. There is huge demand for resources, but other sectors of the economy are flat. Moreover, two decades ago Australians spent around 11% of their income on regular payments (loan repayments, rent, bills etc). Now the figure is 18.6% (above the US where it is 18.5%) and household debt has risen to a record 160% of disposable income. Fine, if interest rates remain low, but a potential disaster if they start to rise significantly. A similar thing is happening in the UK where some industries are booming while others are fighting for their life, while in the US high growth at the top end is masking what could be termed a recession at the bottom. So what’s the idea here? On a superficial level it’s simply that two opposites can happily co-exist. The interesting point is not that this is happening but where it’s happening and where it might happen next.

On another level, questions are also being raised about a system that can deliver great wealth for corporations, but leave a trail of destruction for everyone else. Then again, is this really anything new?

Ref: Various including The Australian (Aus) 4-5 June 2005, ‘Our retro economy is still swinging’, G. Megalogenis. www.theaustralian.com.au; Barron’s (US) 7 February 2005, ‘Handling the truth’, J. Ablan; Sydney Morning Herald (Aus), 9-10 July 2005, ‘Decade of debts eats family cash’, M. Wade. www.smh.com.au

Where small loans are big business

Gramen bank in Bangladesh (est. 1976) started the trend for micro-lending and has spawned a host of successful imitators offering loans as small as US $25 which help people set up small businesses to fight their way out of poverty. Estimates vary, but the number of people helped by such loans is in the region of 70-750 million people. Apart from the small size of loans, one of the clever features is that the loans are ‘guaranteed’ by the local community rather than the individual. The latest development in micro-lending in Asia is that customers (often women) are telling the banks that they want larger loans to set up larger businesses. In some cases this means US $10,000 rather than US $50.

In many rural areas, credit is almost unavailable and the skills and resources needed to set up a business are hard to come by. Nevertheless, the dream of running one’s own business is a dream shared by many.

This is a win-win for financial services companies who can sign up highly credit-worthy customers and in return supply much needed skills and advice at the same time.

Ref: New York Times (US), 14 January 2005, ‘Macro demand for microcredit’, B. Cummings. www.nytimes.com. See also New York Times, 21 January 2005 ‘Capital gains momentum in SouthEast Asia’, W. Arnold.

Foreign currency to go

Mastercard has teamed up with a company called the International Currency Exchange to launch a pre-paid debit card called Cash2Go. The card can be loaded with a specific currency before you travel and then used at ATMs at your destination. The card is accepted in 120 countries. Meanwhile, GE Money-backed Wizard in Australia has launched a credit card that does not charge customers for withdrawals in foreign countries.

Ref: Online Banking Review (Aus), July/Aug 2005, ‘Global Roundup: Pre-paid global card’, www.onlinebankingreview.com.au